Some memories don’t knock—they just kick the door open, Cuban-heeled black suede winkle-pickers and all.

Welcome back to Needle Drops, where the stories are scruffy, half-remembered, but still spark louder than they have any right to.

This one begins with concrete floors, dirty sleeping bags, and the kind of cold that gnaws through even the thickest punk bravado.

It was Futurama 2 Festival, Queens Hall, Leeds, 1980.

The biggest indoor venue in Europe back then—a cavernous ex-tram depot packed with punks, beer cans, and enough second-hand smoke to cloud out the stage lights.

The first day had started well. We’d parked Brian’s van outside X Clothes, a punk clothing palace that was like Leeds’ own version of London’s Sex boutique — a scrappier, northern outpost where wanna-be punks cobbled together their own armor from safety pins, tartan scraps, and borrowed swagger.

Although the tickets said you couldn’t bring alcohol into the venue, we decided to risk it and clubbed together for a bottle of off-brand vodka, hidden in Roz’s bag.

We hadn’t thought about them having security guards. Sure enough, when it was our turn to be frisked and searched, the vodka was discovered.

They were about to confiscate it, but I had the bright idea of asking whether we could drink it instead.

They looked at each other, shrugged, and nodded.

We stood there at the entrance, passing the bottle around, each of us taking big swigs and gasping them down until it was all gone.

After that, the day became a blur—the loudest thing I’d ever heard.

It was as if Spinal Tap had retrofitted their amps to go all the way up to twelve.

Somewhere between the echoing walls and the trash-strewn floors, you could stumble into sets by Soft Cell, U2, Siouxsie and the Banshees, or a dozen bands you’d never hear of again—but for one weekend, it all mattered equally.

Through the haze, I remember catching Altered Images, Clock DVA (local Sheffield lads), Echo & The Bunnymen, Hazel, O’Connor, U2, and Siouxsie & The Banshees headlining.

I vaguely recall Soft Cell playing in what looked like a padded cell tucked behind the main stage—and desperately trying to sleep through the sheer sonic assault that was Robert Fripp & The League of Gentlemen.

When the music finally crashed to a halt around 2 a.m., we found a patch of floor where beer hadn’t been spilled (or worse) and collapsed—me, Roz (my girlfriend, later my wife), Brian, and Little Pete—all crammed into two zipped-together sleeping bags like some misshapen caterpillar.

It was filthy. It was freezing. It was perfect.

The plan was simple: wake up, find the van, change into cleaner clothes, and dive back into the music.

Except the van—the ex-GPO one Brian had lovingly painted in leopard spots—was gone.

At first, hope kept bobbing up, stubborn as a bad haircut.

“It’s probably just around the next corner,” someone would say.

Or, “Maybe we parked on a different street?”

But when we found ourselves standing outside X Clothes—the place we’d spent most of our money the day before—and the van wasn’t there, it hit us.

We hadn’t misplaced it.

We were the ones misplaced now.

We trudged to the nearest police station, a sleepy old building that looked like it had been lifted straight out of Dixon of Dock Green, clock stuck at 1958.

Behind the desk, a lone copper in rolled-up sleeves took our statement—patient, professional.

At least until he turned, pushed open a frosted glass door, and shouted back into the station house:

"Come on out here, lads! We’ve got the bloody Quality Street Gang in here!"

Apparently, to his nicotine-stained, Old Spice-scented colleagues, four scruffy punks in torn jackets and technicolor haircuts looked less like crime victims and more like a box of fancy chocolates.

Honestly?

He wasn’t wrong.

After being good-naturedly heckled by a lineup that looked like rejects from The Sweeney, the desk sergeant gave his advice:

"Go home, lads. Forget about the rest of the festival."

So we did.

The train ride back was almost silent.

No jokes. No big plans. Just the steady clatter of the tracks and a strange hollowness, like we’d left more behind in Leeds than just a van.

Maybe it was the first real crack in that feeling of scrappy invincibility we all wore like second skins.

Later that afternoon, Brian called.

The police had found the van—joyriders, they said—and he and Pete were already heading back to Leeds to retrieve it.

Maybe, just maybe, they'd even catch Gary Glitter’s set that night.

When they got there, though, they found the van sitting dead in the police lot. The lights had been left on, and the battery was as flat as a pancake.

No AA membership, no jump leads, no miracles.

So they did the only thing they could: trudged back to Queens Hall, caught Gary Glitter after all, and then without the sleeping bags, tried to get some sleep on the sticky floor.

Because sometimes punk rock isn’t about the music or the clothes.

It’s about sticking around—even when the map’s gone missing, and you’re not sure where you’re supposed to be anymore.

More soon.

— Robert

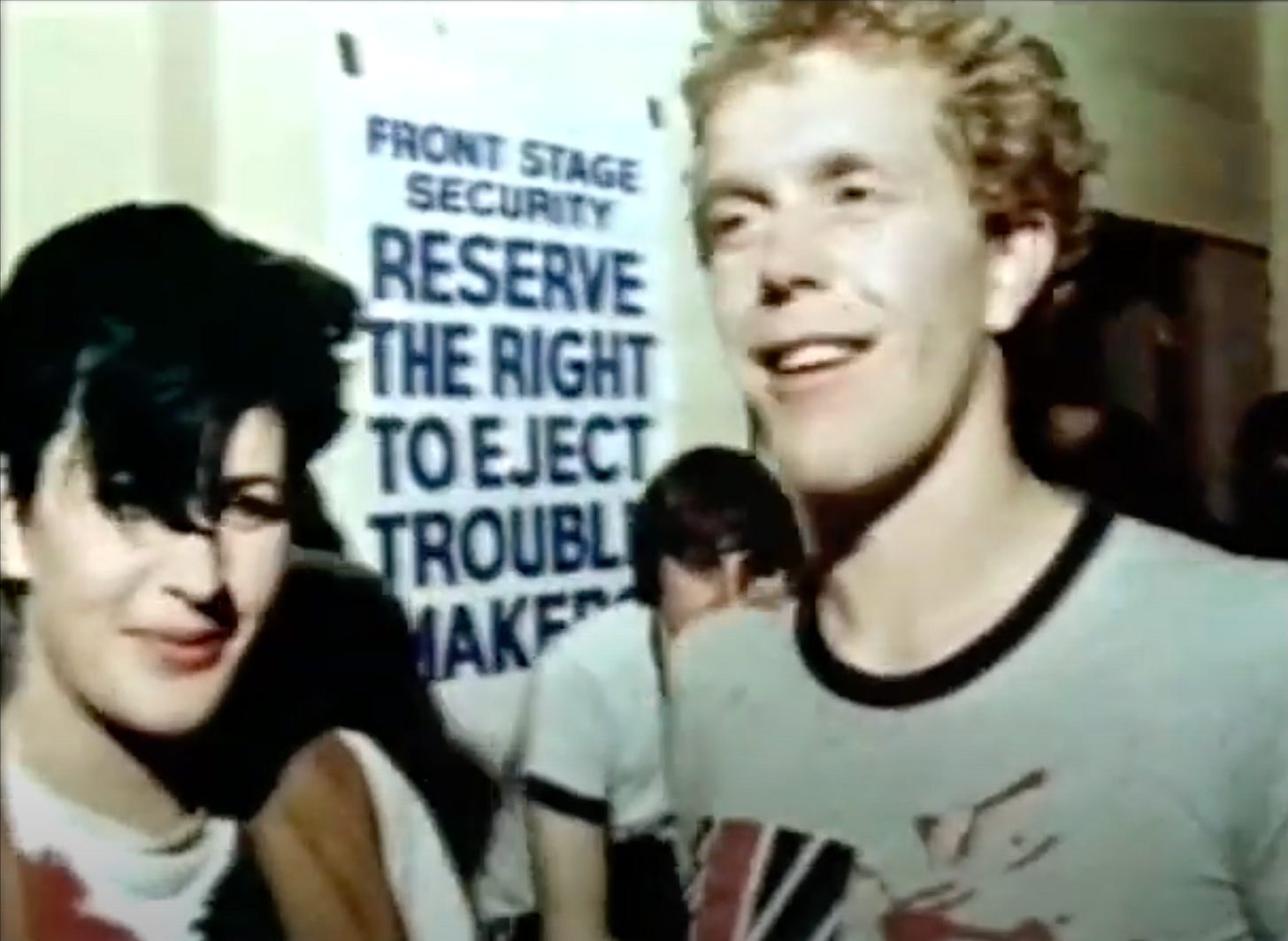

P.S. While you don’t quite get to experience the smokiness or the sticky floors (honestly, nostalgia isn’t all that it’s cracked up to be), here are some videos I found:

Some great nostalgia there! I had a red mohair jumper from X clothes. They had one in Sheffield too. Great piece again. Love it!