He didn’t ask. Just wandered over as we slowed on Hepthorne Lane, slipping into a Top Gear-style review—handling, performance, ride—before finally arriving at the boot.

“Boot on these is like a glove compartment with ambitions.”

No one asked. That never stopped Hicksy. He moved like someone who’d skipped ahead in the manual and assumed the rest of us would catch up.

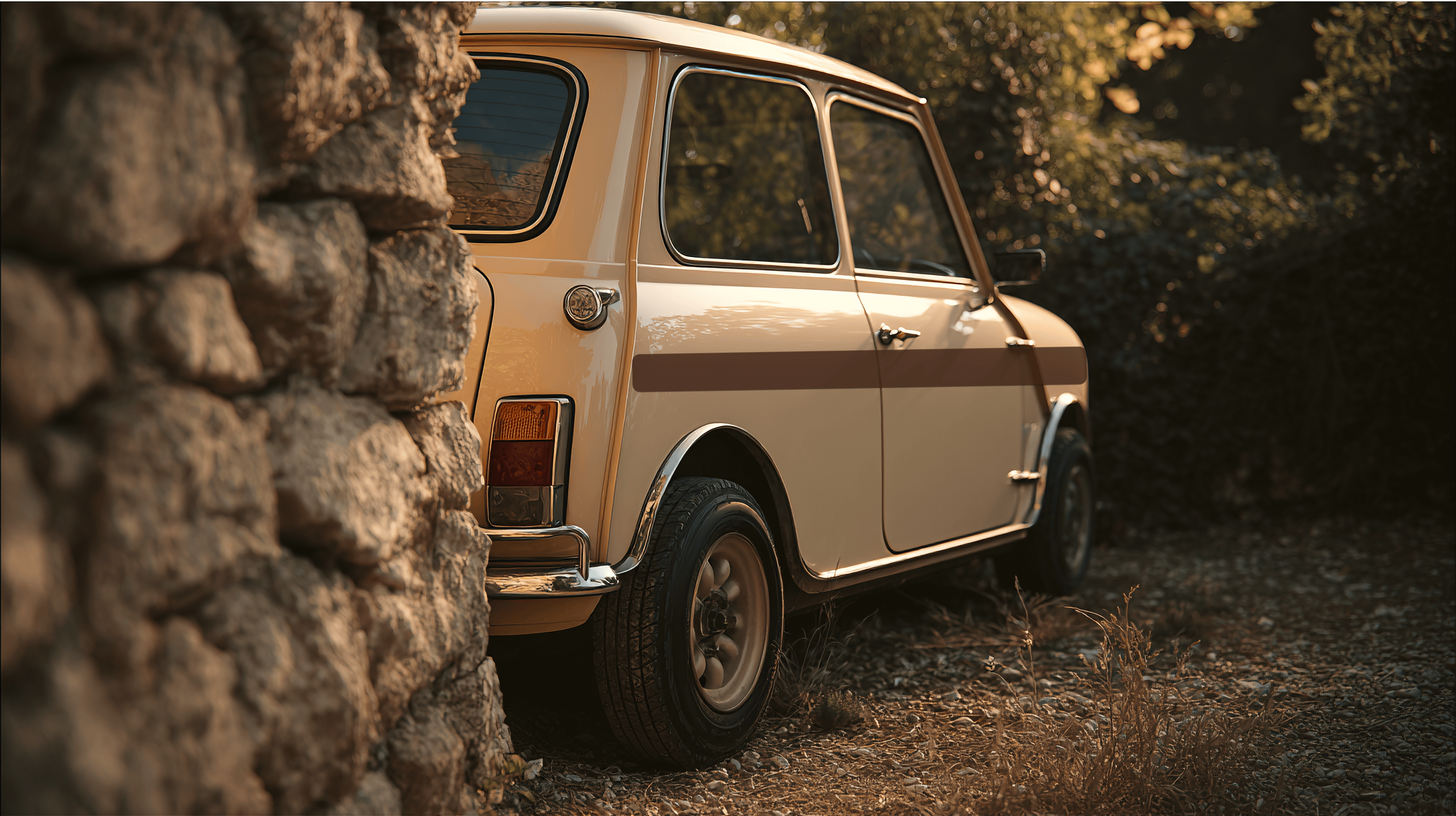

It was the middle of the day, maybe 2pm. Bright, warm, quiet in that suspicious way afternoons sometimes are. We were just back from the tops—Chatsworth side, moors still hazy with early afternoon heat. Andy in the front. Johnny folded up like cargo in the back. Me driving the Mini Cooper that I’d originally called Clarissa. People found that strange, pretentious, stupid—or all of the above. So I changed it to Min. Beige, with a chocolate brown go-faster stripe I’d painted myself—masking tape, spray cans of primer and top coat, a whole Saturday given to speed’s illusion. It wasn’t quick, but it looked like something someone had meant.

We spotted him from a distance—Hicksy was always recognizable by his gait, a kind of loose-limbed defiance of pavement logic. I crept beside him at walking pace, let him study the silhouette. He circled once, slowly, like the car might confess something if stared at long enough. He tapped the boot once, then said: “Bet I could fit in there.”

No one had asked. No one doubted him. But the moment he said it, it felt like something that had to be proven.

He didn’t take anything off. Just ducked, folded, twisted himself in. Even skinny as he was, it was astonishing. All of him disappeared except one arm—stiff, jutting out—like those novelty limbs people wedge in tailgates for a laugh.

Only this wasn’t a joke. Hicksy was actually in there.

He was grinning, ready to declare victory, when someone—maybe Andy, maybe me—said: “You’ve got to be driven in it. Otherwise it doesn’t count.”

That logic held. So we got back in. Engine on. I drove the half-mile to the Blue Bell with Hicksy in the boot—arm sticking out, voice muffled but constant, offering commentary we mostly ignored.

We pulled into the lot of the Blue Bell—a 15th-century pub with a sagging roof, its ghost stories half-remembered and more than half-embellished. It was where all of us had been served our first pints. Under-age drinking was just something you did back then, like starting to take an interest in girls, or getting acne.

I remembered being woken from my bed and shoved into a too-big coat by my brother and his mates as they set out for their own first pints. They’d filled my head with stories about the pirate’s grave—there wasn’t one, though there is a stone in the churchyard marked with a skull and crossbones—and the ghost that haunted the shortcut through the cemetery. Then they left me outside in the dark with a Coke and a packet of crisps while they went in. I sat on the low wall, listening to the laughter spill out through the warped door, and waited for the light above it to flicker.

And now here we were, years later, parking a little too close to that same wall. No Coke, no crisps. Just Hicksy, boxed and booted, his arm sticking out like punctuation.

I was about to kill the engine when I had an idea.

I pulled forward, turned around, and reversed—inch by inch—until the bumper kissed the pub’s back wall.

The boot on the old Mini opened downward, like a glove box—little chains on either side. Reversing into the wall meant it couldn’t open at all.

We got out. Looked at each other. A moment hung.

“Are you not coming with us?” one of us asked, and the three of us collapsed into laughter.

Ignoring Hicksy’s muffled objections—now loud, now impressively creative—we walked into the pub and ordered a round of beers.

“Do you think we should go and get him out?” someone asked eventually.

Pause.

“Should we have another beer first?”

That seemed funnier.

But as the pints arrived, so did the guilt. We drank quickly.

There’s something about that time in your life when even being the butt of the joke feels like being let in. Like being seen.

When we finally went back out, I wasn’t sure what to expect. Hicksy’s arm was still there, accusingly lifeless. We moved the car. Opened the boot.

He erupted—a full-throttle, expletive-laced monologue that had clearly been building the whole time we were in the pub. The kind of fury that needs an audience. (We didn’t tell him about the second round.)

And yet—even then—there was a glint. A flash of something like pride.

He’d done it. Squeezed himself into a tiny boot. Got driven to a pub. Got parked against a wall. Became legend.

I haven’t seen Hicksy in years. But an old school friend mentioned, not long ago, that he’d spotted him.

I do wonder, sometimes, if he ever tells that story.

I hope he remembers it like we did—louder, stranger, and somehow… perfectly logical.

Love this one, Robert! Made me laugh, and empathize with Hicksy, who unknowingly was the star of the show. Nicely done, nicely told!